People saw a new colour for the first time in 2025

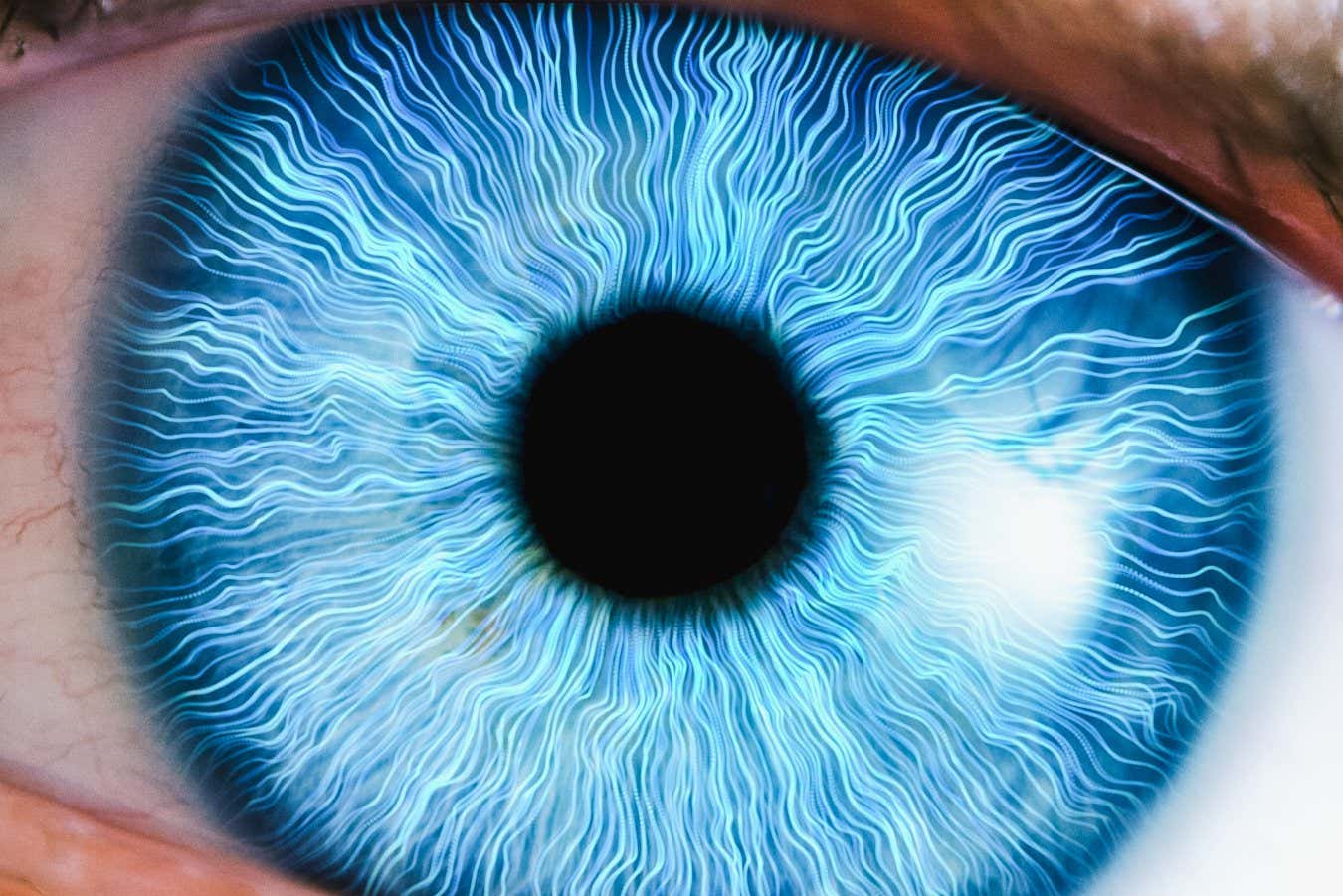

We perceive colour using input from the cone cells in our retinas Shutterstock/Kitreel In April, a team of researchers

We perceive colour using input from the cone cells in our retinas

Shutterstock/Kitreel

In April, a team of researchers reported a device enabled them to witness an intense green-blue colour that had never been seen by humans before. After the announcement, they were bombarded by requests from the public to see the colour for themselves.

The device could enable people with some kinds of colour blindness to experience typical vision, and could even allow people with typical vision to perceive a wider range of hues. “We’re very interested in expanding the dimensions of the colour experience,” says Austin Roorda at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

In most people, the retina at the back of the eye contains three types of cone cells – called S, M and L – that each detect light with a different range of wavelengths. Our brains create our perception of colour based on the signals from these three types of cones.

The range of the visible spectrum detected by M cone cells overlaps with the ranges of the other two types, so we don’t normally receive signals from the M cells alone.

Roorda and his colleagues used an extremely precise laser to specifically activate about 300 M cones in a small square patch of the retina. This patch corresponds with a part of the visual field equivalent to the size of your fingernail at arm’s length, says Roorda.

When five of the researchers used the device, they saw a blue-green colour that was more intense than anything they had seen before, which they named “olo”. This was verified using a colour-matching test where they compared olo with the full spectrum of shades in the visible spectrum.

“That was really quite a stunning moment,” says Roorda, who has seen olo more times than anyone else, owing to his key role in developing the system. “The most saturated natural light just looked pale by comparison.”

After the achievement made a splash in the media, the team received dozens of requests from people – including artists – to view olo. But it takes several days to get the system set up for a new person, so the team couldn’t afford to accept these, says Roorda.

Instead, they are focusing on two ongoing experiments. In the first, they will test whether the device could enable people with colour blindness to temporarily experience typical vision. Certain kinds of colour blindness are caused by only having two types of cones rather than three. “We would play some of the cones belonging to a single cone type a little differently to others of that cone type, and we think this will send signals to the brain as if they had a third cone type,” says Roorda. The hope is people’s brains will interpret those signals as new colours they haven’t perceived before, he says.

The team is also exploring whether a similar approach could allow people with three cone types to experience the world as if they have four, which some people have naturally, enabling them to see a wider range of hues. Results from both experiments should be available next year, says Roorda.

Topics: