Genetic trick to make mosquitoes malaria resistant passes key test

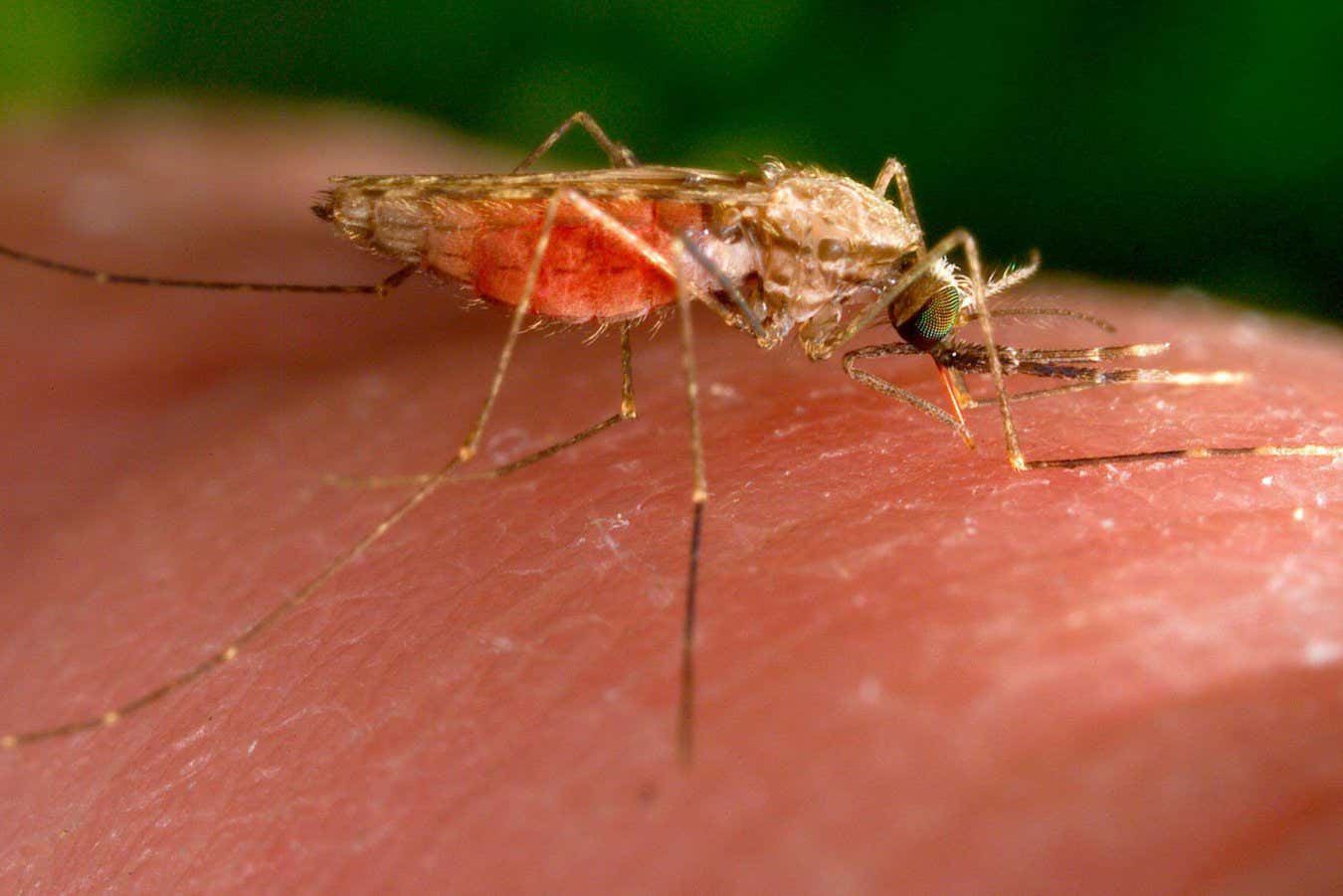

Scientists tested the approach on Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, which are endemic to Tanzania, where they transmit malaria James Gathany/CDC

Scientists tested the approach on Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, which are endemic to Tanzania, where they transmit malaria

James Gathany/CDC via AP/Alamy

A genetic technology known as a gene drive could help prevent malaria by spreading genes in wild mosquitoes that stop them transmitting the parasite. Tests in a lab in Tanzania have now confirmed that one potential gene drive should achieve this if it were released in the country.

“It would be a game-changing technology, that’s for sure,” says George Christophides at Imperial College London.

A specific piece of DNA in the genome of an animal is normally passed on to only half its offspring, because a parent’s DNA is divided in half among egg or sperm. Gene drives increase this proportion, meaning a bit of DNA can spread rapidly through a population even if it provides no evolutionary benefit.

There are many natural gene drives that work via all kinds of mechanisms – perhaps even in some human populations – and in 2013, biologists developed artificial gene drives using CRISPR gene-editing technology, which works by copying pieces of DNA from one chromosome to another.

The idea is to use these drives to spread bits of DNA that block malaria transmission – but which bits? Christophides reported in 2022 that the development of malaria parasites inside mosquitoes can be greatly reduced by two tiny proteins, one derived from honeybees and the other from the African clawed frog. The added genes for these antimalarial proteins can be linked to the gene for an enzyme that helps mosquitoes digest blood, so the antimalarial proteins are made after a mosquito feeds and get secreted into its gut.

But these tests were done using lab strains of mosquitoes and malarial parasites collected decades ago, so it wasn’t clear if this approach would work in Africa today.

Now, researchers including Christophides and Dickson Lwetoijera at the Ifakara Health Institute in Tanzania have modified local Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes to produce the components of a gene drive based on this approach. The components were kept separate, meaning the gene drive cannot spread, and the mosquitoes were housed in a secure facility.

Tests show robust inhibition of malaria parasites taken from infected children, and also effective copying of the genes for the antimalarial proteins. “So we are now able to say that this technology could work in the field,” says Christophides.

The next step will be to release mosquitoes that produce the antimalarial proteins on an island in Lake Victoria, to see how they behave in the wild. The team is engaging with local communities there as well as carrying out risk assessments, says Lwetoijera. “To date, the political and public support has remained positive.”

The hope is that the gene drive could help eliminate malaria from areas where A. gambiae is the only species spreading malaria, says Christophides. “A gene drive may turn the tide,” he says.

Several other groups are also working on gene drives for controlling malaria, and the technology is also being developed for controlling various pests.

Genetically modified mosquitoes are already being released to control wild mosquito populations in some countries, but these approaches rely on continually releasing very large numbers of the insects.

Topics: