Quantum experiment finally settles a century-old row between Einstein and Bohr

The double-slit experiment demonstrates the quantum nature of reality RUSSELL KIGHTLEY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY A thought experiment that was at

The double-slit experiment demonstrates the quantum nature of reality

RUSSELL KIGHTLEY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

A thought experiment that was at the heart of an argument between famed physicists Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr in 1927 has finally been made real. Its findings elucidate one of the core mysteries of quantum physics: is light really a wave, a particle or a complex mixture of the two?

Einstein and Bohr’s argument concerns the double-slit experiment, which dates back another hundred years to physicist Thomas Young in 1801. Young used this test to argue that light is a wave, while Einstein posited that light is actually a particle. Meanwhile, Bohr’s work in quantum physics boldly proposed that it can, in a sense, be both. Einstein didn’t like this controversial idea and imagined a modified version of Young’s experiment to counter it.

Now, Chao-Yang Lu at the University of Science and Technology of China and his colleagues have performed an experiment that realises Einstein’s idea, using the best tools of modern experimental physics to reveal that quantum objects are as peculiar in their dual wave-and-particle nature as 1920s physicists suspected. “Seeing quantum mechanics ‘in action’ at this fundamental level is simply breathtaking,” says Lu.

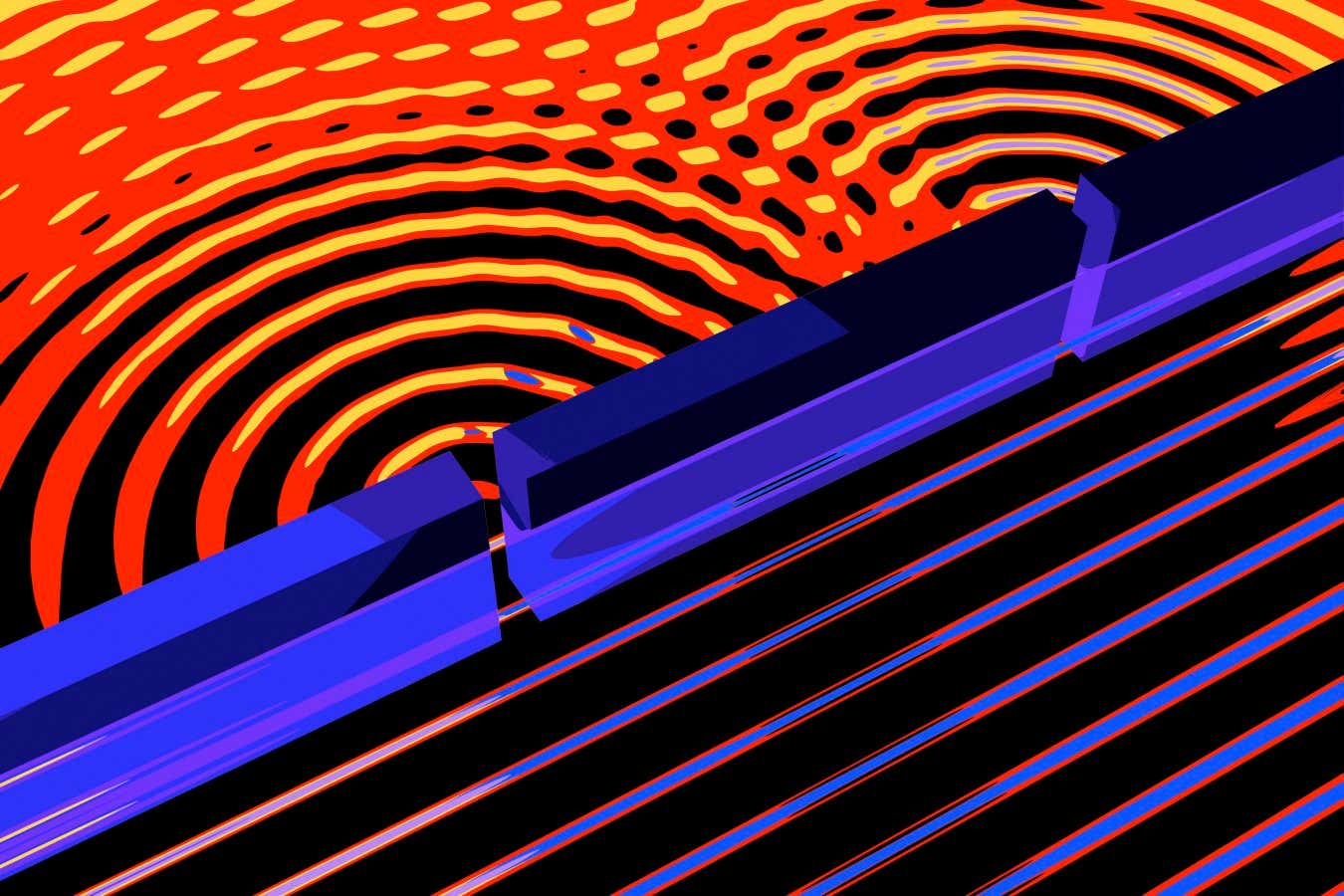

In the classic double-slit experiment, researchers shine light onto a pair of narrow, parallel, horizontally oriented slits positioned in front of a screen. If light were a particle, the screen ought to show a blob of light behind each slit, but Young and countless researchers that followed instead saw an “interference pattern” of alternating dark and light stripes. This indicated that light is more like a wave that spills through the slits, with the screen capturing its ripples clashing into each other. Remarkably, the interference pattern persists even when the light’s intensity is reduced to a single particle of light, or a photon. Does this mean that the perfectly particle-like photon somehow interferes with itself as if it were also a wave?

Bohr argued for the notion of “complementarity” where it is impossible to see the photon’s particle-ness when it is exhibiting wavy behaviour and vice versa. In their debates on whether this truly holds, Einstein imagined placing an additional slit before the usual pair that would be equipped with springs, so it could recoil when the photon entered it. Based on the springs’ motion, physicists could then determine whether the photon went through the top or bottom slit. According to Einstein, this would mean being able to simultaneously describe the photon’s particle behaviour – travelling through a specific slit like a tiny ball would – and its wave behaviour as evidenced by the interference pattern, which would contradict complementarity.

Lu says that his team wanted to build this device at the “ultimate quantum limit”, so they shot a single photon not at a slit, but an atom that could recoil in the same way. Additionally, hitting the atom put the photon into a quantum state equivalent to a mix of moving away from the atom to the left and to the the right, which also produced an interference pattern when it hit a detector. To use an atom in this way, the researchers used lasers and electromagnetic forces to make it incredibly cold, which made it possible to control its quantum properties extremely precisely. This was crucial for testing Bohr’s retort to Einstein: he argued that the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which says that if the change in the slit’s momentum from the recoil was known very well then its position would become very fuzzy and vice versa, could destroy the interference pattern.

“Bohr’s counterargument was brilliant. But the thought experiment remained theoretical for almost a century,” says Lu.

By tuning the lasers, Lu and his colleagues could control the uncertainty in the momentum of the atom-as-slit. In doing so, they found that Bohr’s assertion was correct and they could erase the interference pattern by tweaking the fuzziness of its momentum. Strikingly, the researchers also used this tunability to access a more in-between regime where they could measure some recoil information and also see a blurry version of the interference pattern. Here, the photon was effectively exhibiting both wave and particle properties at once, says Lu.

“The real interest is in [this] in-between,” says Wolfgang Ketterle at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Earlier this year, he and his colleagues carried out a variation of Einstein’s experiment. They used ultracold atoms controlled by lasers to implement a version of Einstein’s experiment where it is the pair of slits that can move. Whereas Lu and his colleagues used a single atom to scatter light in two directions, here, two atoms scattered light in the same direction, and the effect of the photon hitting each atom could be detected from the changes in their quantum states. Ketterle says this is a conceptually different way to probe wave-particle duality and more clearly records what the photon did because this “which-way” information becomes stored in one of the two separate atoms, but it is a slight departure from Einstein’s original idea.

He and his colleagues also experimented with suddenly turning off their lasers – equivalent to removing the springs from the moveable slits – then shooting photons at the atoms. Bohr’s conclusion still held as the exchange of momentum between the atoms and the photon, plus the uncertainty principle, could still “wash out” the interference pattern’s stripes. This spring-less version of Einstein’s idea hadn’t been tested previously, says Ketterle. “In atomic physics, with cold atoms and lasers, we have real opportunities to showcase quantum mechanics with clarity which was not possible before.”

Philipp Treutlein at the University of Basel in Switzerland says that the two experiments powerfully showcase some of the fundamentals of quantum mechanics. “With our modern understanding, we know the answer to how quantum mechanics works at the microscopic scale. But it always makes a difference if you see it for real, so to speak, if somebody actually does that experiment.” The experiment by Lu and his team conceptually matches the drawings that remain in the historical record of debates between Bohr and Einstein and behaves exactly in the way quantum mechanics predicts it should behave, he says.

For Lu, there is still more to explore, for example classifying the quantum state of the slit in even more detail, as well as increasing its mass. But the experiment also holds immense educational value. “Above all, I hope it conveys the sheer beauty of quantum mechanics,” he says. “If a few more young people watch the interference pattern appear or disappear in real time and say, “Wow, nature really works like that,” then the experiment has already succeeded.”

Topics: