30 Years Ago: Clementine Changes Our View of the Moon

In 1994, a joint NASA and Department of Defense (DOD) mission called Clementine dramatically changed our view of the

In 1994, a joint NASA and Department of Defense (DOD) mission called Clementine dramatically changed our view of the Moon. As the first U.S. mission to the Moon in more than two decades, Clementine’s primary objectives involved technology demonstrations to test lightweight component and sensor performance. The lightweight sensors aboard the spacecraft returned 1.6 million digital images, providing the first global multispectral and topographic maps of the Moon. Data from a radar instrument indicated that large quantities of water ice may lie in permanently shadowed craters at lunar south pole, while other polar regions may remain in near permanent sunlight. Although a technical problem prevented a planned flyby of an asteroid, Clementine’s study of the Moon proved that a technology demonstration mission can accomplish significant science.

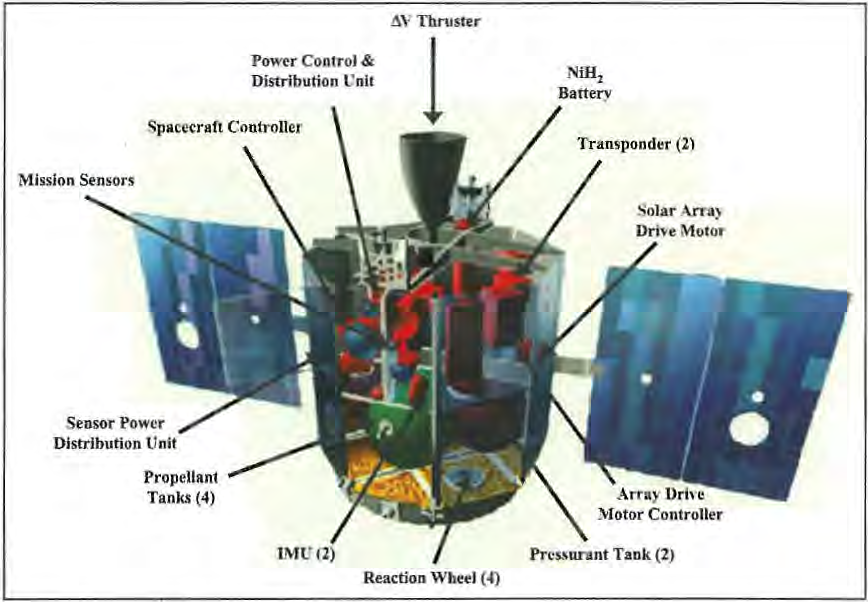

Left: The Clementine engineering model on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C. Image credit: courtesy NASM. Right: Schematic illustration showing Clementine’s major components and sensors.

The DOD’s Strategic Defense Initiative Organization, renamed the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization in 1993, directed the Clementine project, formally called the Deep Space Program Science Experiment. The Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) in Washington, D.C., managed the mission design, spacecraft manufacture and test, launch vehicle integration, ground support, and flight operations. The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in Livermore, California, provided the nine science instruments, including lightweight imaging cameras and ranging sensors. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Beltsville, Maryland, provided trajectory and mission planning support for the lunar phase, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, provided trajectory and mission planning for the asteroid encounter and deep space communications and tracking through the Deep Space Network. Clementine’s primary planned mission involved the testing of new lightweight satellite technologies in the harsh deep space environment. As a secondary mission, Clementine would observe the Moon for two months using its multiple sensors, then leave lunar orbit and travel to 1620 Geographos, a 1.6-mile-long, elongated, stony asteroid. At a distance of 5.3 million miles from Earth, Clementine would fly within 62 miles of the near-Earth asteroid, returning images and data using its suite of sensors.

Left: Technicians prepare Clementine for a test in an anechoic chamber prior to shipping to the launch site. Middle: Workers lower the payload shroud over Clementine already mounted on its Titan IIG launch vehicle. Right: Liftoff of Clementine from Vandenberg Air Force, now Space Force, Base in California.

The initial idea behind a joint NASA/DOD technology demonstration mission began in 1990, with funding approved in March 1992 to NRL and LLNL to start design of Clementine and its sensors, respectively. In an incredibly short 22 months, the spacecraft completed design, build, and testing to prepare it for flight. Clementine launched on Jan. 25, 1994, from Space Launch Complex 4-West at Vandenberg Air Force, now Space Force, Base in California atop a Titan IIG rocket.

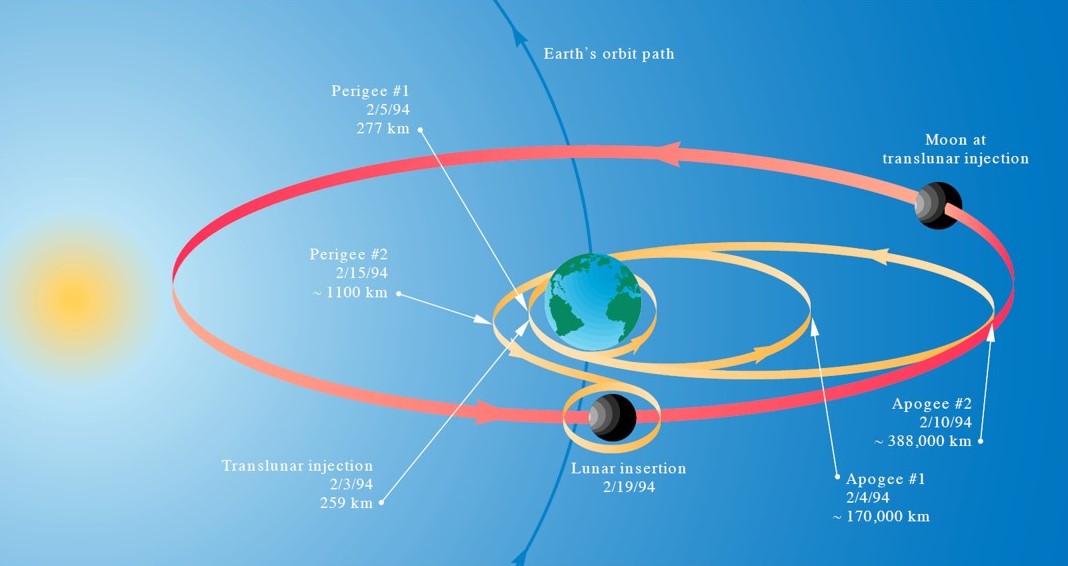

Trajectory of Clementine from launch to lunar orbit insertion. Image credit: courtesy Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

The spacecraft spent the next eight days in low Earth orbit checking out its systems. On Feb. 3, a solid rocket motor fired to place it on a lunar phasing loop trajectory that included two Earth flybys to gain enough energy to reach the Moon. During the first orbit, the spacecraft jettisoned the Interstage Adapter Subsystem that remained in a highly elliptical Earth orbit for three months collecting radiation data as it passed repeatedly through the Van Allen radiation belts. On Feb. 19, Clementine fired its own engine to place the spacecraft into a highly elliptical polar lunar orbit with an 8-hour period. A second burn two days later placed Clementine into its 5-hour mapping orbit. The first mapping cycle began on Feb. 26, lasting one month, and the second cycle ended on April 21, followed by special observations.

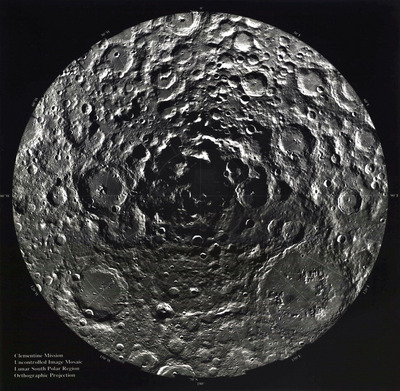

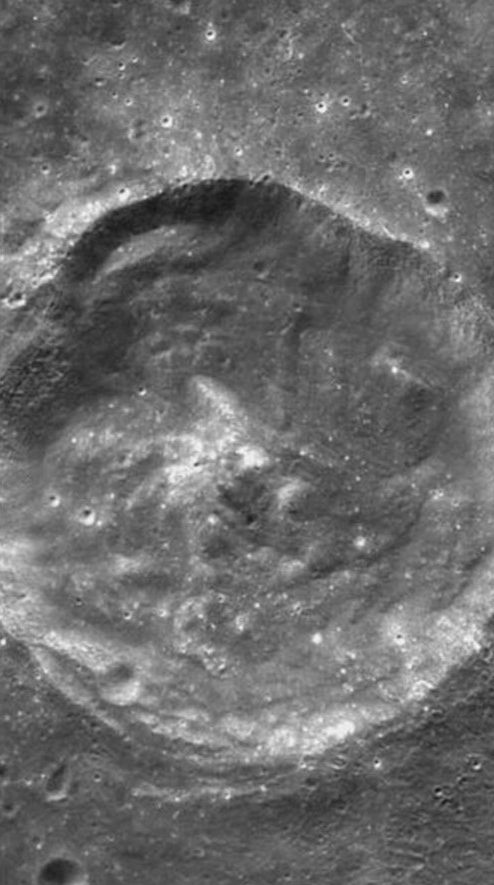

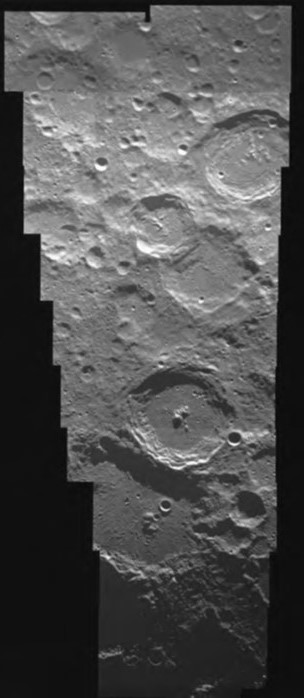

Left: Composite image of the Moon’s south polar region. Middle left: Image of Crater Tycho. Middle right: Image of Crater Rydberg. Right: Composite image of the Moon’s north polar region.

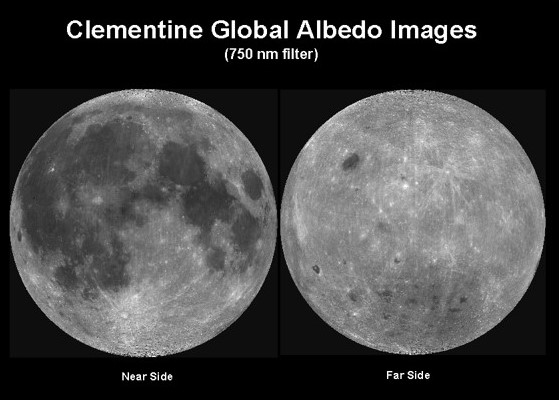

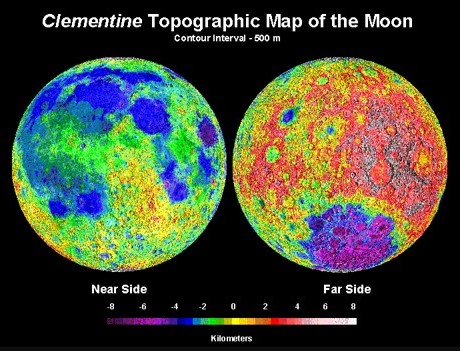

During the first month of mapping, the low point of Clementine’s orbit was over the southern hemisphere to enable higher resolution imagery and laser altimetry over the south polar regions. Clementine adjusted its orbit to place the low point over the northern hemisphere for the second month of mapping to image the north polar region at higher resolution. Clementine spent the final two weeks in orbit filling in any gaps and performing extra studies looking for ice in the north polar region. For 71 days and 297 lunar orbits, Clementine imaged the Moon, returning 1.6 million digital images, many at a resolution of 330 feet. It mapped the Moon’s entire surface including the polar regions at wavelengths from near ultraviolet through visible to far infrared. The laser altimetry provided the first global topographic map of the Moon. Similar data from Apollo missions only mapped the equatorial regions of the Moon that lay under the spacecraft’s orbital path. Radio tracking of the spacecraft refined our knowledge of the Moon’s gravity field. A finding with significant application to future exploration missions, Clementine found areas near the polar regions where significant amounts of water ice may exist in permanently shadowed crater floors. Conversely, Clementine found other regions near the poles that may remain in near perpetual sunlight, providing an abundant energy source for future explorers. The Dec. 16, 1994, issue of Science, Vol. 266, No. 5192, published early results from Clementine. The Clementine project team assembled a series of lessons learned from the mission to aid future spacecraft development and operations.

Left: A global map of the Moon created from Clementine images. Right: A global topographic map of the Moon based on Clementine data.

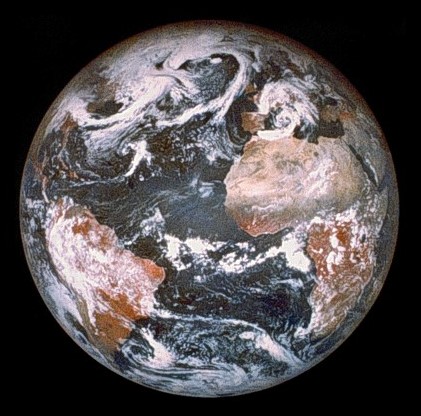

Left: Composite image of Earth taken by Clementine from lunar orbit. Middle left: Colorized image of the full Earth over the lunar north pole. Middle right: Color enhanced view of the Moon lit by Earth shine, the solar corona, and the planet Venus. Right: Color enhanced image of the Earthlit Moon, the solar corona, and the planets Saturn, Mars, and Mercury.

Its Moon observation time over, Clementine left lunar orbit on May 5, heading for Geographos via two more Earth gravity-assist flybys. Unfortunately, two days later a computer glitch caused one of the spacecraft’s attitude control thrusters to misfire for 11 minutes, expending precious fuel and sending Clementine into an 80-rotations-per-minute spin. The problem would have significantly reduced data return from the asteroid flyby planned for August and managers decided to keep the spacecraft in an elliptical geocentric orbit. A power supply failure in June rendered Clementine’s telemetry unintelligible. On July 20, lunar gravity propelled the spacecraft into solar orbit and the mission officially ended on Aug. 8. Ground controllers briefly regained contact between Feb. 20 and May 10, 1995, but Clementine transmitted no useful data.

Despite the loss of the Geographos flyby, Clementine left a lasting legacy. The mission demonstrated that a flight primarily designed as a technology demonstration can accomplished significant science. The data Clementine returned revolutionized our knowledge of lunar history and evolution. The discovery of the unique environments at the lunar poles, including the probability of large quantities of water ice in permanently shadowed regions there, changed the outlook for future scientific missions and human exploration. Subsequent science missions, such as NASA’s Lunar Prospector and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, China’s Chang’e spacecraft, and India’s Chandrayaan spacecraft, all built on the knowledge that Clementine first obtained. Current uncrewed missions target the lunar polar regions to add ground truth to the orbital observations, and NASA’s Artemis program intends to land the first woman and the first person of color in that region as a step toward sustainable lunar exploration.