2026 will shed light on whether a little-known drug helps with autism

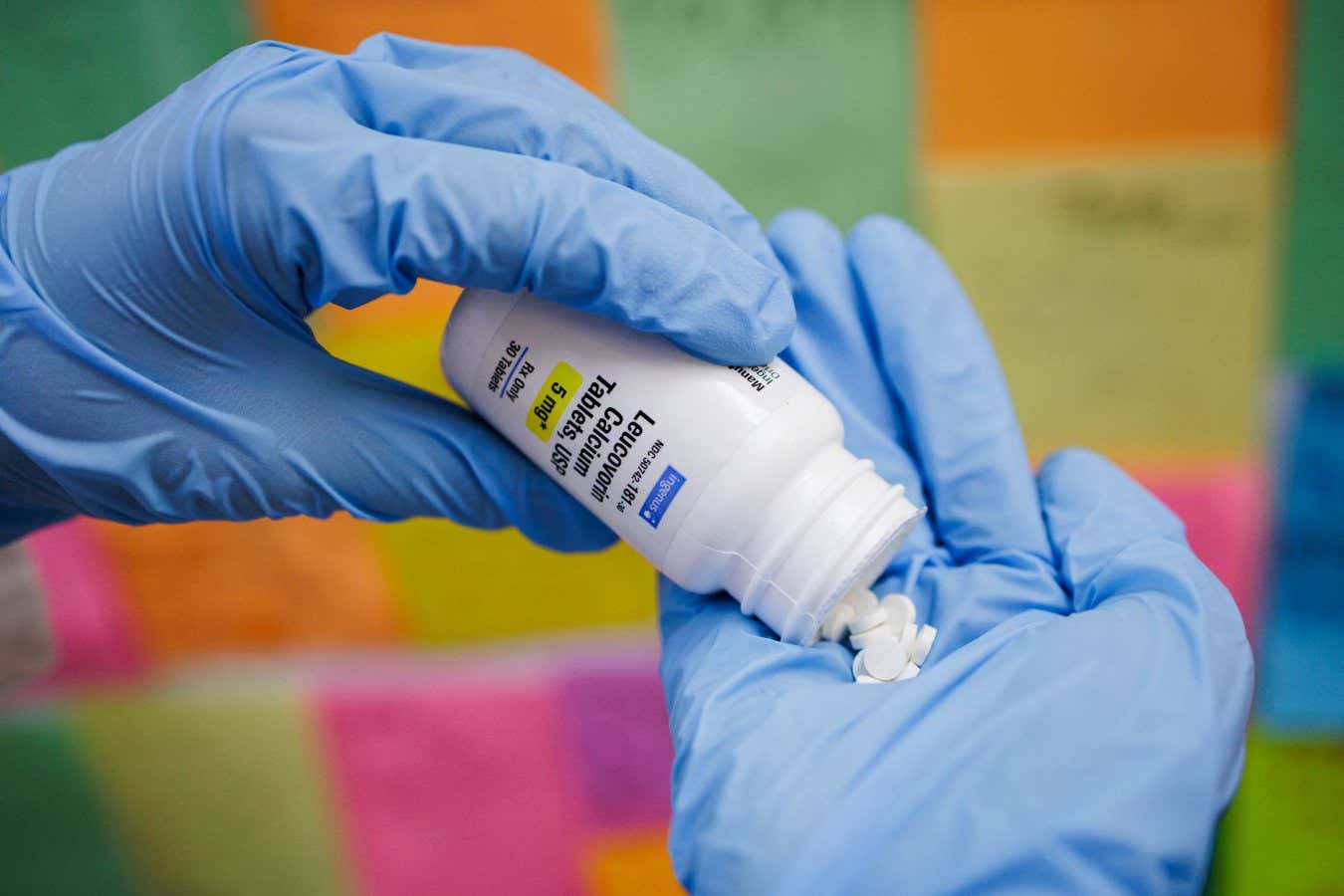

You might not have heard of leucovorin, but it is being championed by the US government to address rising

You might not have heard of leucovorin, but it is being championed by the US government to address rising rates of autism

Hannah Beier/Reuters

The US government made waves last year when it announced it would be approving the little-known drug leucovorin for children with cerebral folate deficiency, a condition that appears to be connected to autism.

The decision left many doctors wary because it was based on evidence from just a few small studies. But we could soon receive more insight into the drug’s potential, as results from the largest trial of leucovorin for autism are expected in the first half of 2026.

Autism became a focal point of US health policy in 2025 after President Donald Trump appointed Robert F. Kennedy Jr to lead the country’s top health agencies. Kennedy, who has falsely blamed vaccines for rising autism rates, pledged in April last year that he would identify the causes of autism by the end of September 2025.

That month, the government announced it was planning to approve leucovorin for people with cerebral folate deficiency, a condition some research suggests affects up to 40 per cent of autistic people. It interferes with vitamin B9 uptake in the brain, leading to symptoms similar to some characteristics of autism, such as communication and sensory processing difficulties.

The US Food and Drug Administration declined to comment on where the approval process currently stands.

Leucovorin is already approved for treating some other kinds of vitamin B9 deficiencies, as well as side effects from some cancer medications. A handful of small trials have also suggested it can ease some difficulties experienced by autistic people.

For example, a 2016 study used two daily doses of leucovorin to treat 23 autistic children with language impediments. After 12 weeks, 65 per cent of them saw a clinically meaningful improvement in verbal communication, compared with only about a quarter of 25 children who received a placebo.

“While promising, it is important to note that leucovorin is not a cure for ASD [autism spectrum disorder] and may only lead to improvements in speech-related deficits for a subset of children with ASD,” the US Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement released after the announcement.

So far, studies have only tested the drug in a few dozen autistic children, so researchers have expressed scepticism about the US government’s decision to approve its use. “The evidence right now is very limited and very inconsistent,” says Alycia Halladay at the Autism Science Foundation in New York.

Richard Frye at Rossignol Medical Center in Arizona and his colleagues are now testing leucovorin in 80 autistic children between the ages of 2.5 and 5. This trial is a significant bump in size, and while some researchers have reservations that it isn’t quite large enough, it is expected to provide a clearer picture.

About half of the children will receive the drug for 12 weeks, while the rest get a placebo. Then, all the participants will take leucovorin for a further 12 weeks to provide additional safety data.

The researchers are mainly looking for changes in social communication, as reported by parents via a standard questionnaire. They will also track other signs of autism, such as irritability, hyperactivity, repetitive behaviours, sensory sensitivities and restricted interests.

Not only could this trial improve our understanding of whether leucovorin helps autistic children, but it could also answer lingering questions about the drug’s safety.

While leucovorin is widely considered safe, little is known about its side effects in autism specifically. “The number of families that have participated in these [past] studies have not been adequate to do a full safety study,” says Halladay.

In the trial, Frye and his colleagues are assessing for potential side effects every two weeks for the first 12 weeks, then every four weeks thereafter. They are also collecting routine blood samples to monitor for any changes in blood clotting, immune response or organ function.

Assuming leucovorin does lead to benefits for autistic children, the mechanism behind this – beyond enhancing vitamin B9 in the brain – will be assessed with scans carried out before and after the trial.

“We don’t know exactly what leucovorin is doing, but what we think is happening is that the brain is getting more connections,” says Frye.

When it comes to how useful the trial will be, however, scientists are conflicted. “There currently is no treatment for core symptoms of autism,” says Frye. “All the medications we have are just kind of Band-Aids that treat symptoms. This could be a treatment that not only improves symptoms for these kiddos but actually treats some of the underlying mechanisms,” he says.

Halladay, on the other hand, worries that the sample size of 80 children is still too small to draw meaningful conclusions, especially given that the trial is being carried out at just one site in Arizona. “I think that this is a good move in the right direction, but I do think that we are going to need additional studies done by additional people at other sites,” she says.

Topics: